Teacher Reflections on Iran Module

When I joined the READI project, using multiple texts was not a new thing in my history classroom. My curriculum and instruction graduate courses had focused on historical thinking and promoted the use of text sets to explore controversies and historical ambiguities. I was familiar with the skills of sourcing, corroboration and contextualization. In my early years of teaching, I had been fortunate to be in a department that had built interesting text sets on topics appropriate for World History. Those text sets consisted mostly of primary sources, but included some secondary sources. Once or twice in a unit, my students would read a text set and practice historical thinking skills. Usually there was a specific inquiry question to address, like, “Who won the Battle of the Somme on the first day?” Because I wanted to provide all of my students with access to the curriculum, I did what I had been taught to do in my pre-service teaching program. I modified the texts to make them easier for my students to read. I supported students by providing so much rich context that they already knew what the texts were about before they read them. I answered their questions as they came up and then wrapped up the activity with an overview of what students were supposed to have gained from looking at those texts.

That there might be a different way to think about using texts in my history class hit me in my first day of Reading Apprenticeship professional development. I recognized myself in the description of the teacher who “teaches around the texts.” I had done this with the best of intentions because I did not yet have the skills to support the diverse learners in my classroom to meet the various demands of the complex texts I wanted students to read. I had unwittingly fixed the challenges my students faced in those texts rather than teach them how to grapple with them. Reading Apprenticeship awakened in me a sense of urgency to improve the literacy skills of all students, as I realized the central role that texts should play in the construction of knowledge. Thinking about the future and what my students would be asked to do in college and in their careers, I began to see literacy as central to achieving equity.

I had worked on implementing Reading Apprenticeship in my classroom for two years when I joined the California READI Teacher Inquiry Network, and was subsequently offered the opportunity to form a design partnership with Gayle Cribb as part of Project READI. Gayle was part of the research team. We wanted to design a unit that I would teach in which we could put the design principles from READI into practice. And, we wanted students to experience becoming curious about a contemporary conflict, wanting to know more, and then successfully follow a line of inquiry. We wanted them to know they were capable of understanding a really complicated real-life situation. We wanted them to build knowledge of the context, use the context to iteratively contextualize the conflict, evaluate the sources and think critically about the information they encountered. Our research questions were:

- How much of the intellectual work can we hand over to the students?

- How much of that work can the students take up successfully?

- What would it take, from our design and implementation, and from students, to do so?

When we set out to design the unit, we had to first learn more about the topic, modern Iran and its history. Then, we searched out possible texts for students to read, and analyzed each one for what it demanded of the reader. We then designed the unit, developing essential questions, imagining inquiry questions the students might come up with, exploring possible inquiry questions, considering a logical order for the texts, and determining routines and participation structures that we thought would support the kind of learning we wanted to see. We developed a tentative progression, with multiple paths because we wanted to be responsive to the inquiry developed by the students.

It was in the implementation that the shifts in my practices started. Gayle was by my side, constantly urging me to hand questions back to the students, to prompt them to explain their thinking, and to step away from being the expert in the room. It is important to me to communicate that this was not an easy process, despite having a strong relationship to the research team and a high level of trust in Gayle. I experienced resistance, both from the students, and from myself, and spent a lot of time muddling through middle ground, driven by a sense that this work would, if I could stay the course, promote equity in the classroom.

The 2013 iteration of the Iran unit represents this middle space. While students had been working with texts in my class the whole year, being asked to do so much of the interpretation and synthesizing across texts was a new level of responsibility and intellectual work. I was handing that job over to them, and holding high expectations that they would take it up. I asked them to trust me in the process, and there were many moments when I was working really hard to stay out of the role of content expert and students were trying at least as hard to pull me back in. Internally, I had to re-negotiate my identity in the classroom. If I wasn’t the expert who put it all together in the end for the students, who was I? If I didn’t help them when they asked for help or when they had struggled for a while, what kind of a teacher was I? As I made attempts, pushing myself and my students a little further each time, and beginning to see good results, I started to see myself as a facilitator of sorts versus the fount or verifier of knowledge. Still, I had to keep reminding myself that the goal was to support students to become more independent readers and learners. I had to remind myself that by building their skills, they would be able to access any content.

This was both hard and exhilarating. Hard, because sometimes my students accused me of not helping them, and I felt like I was “not helping” in the ways they wanted. That was challenging, and I had to keep deciding to experiment even as they resisted. It was exhilarating because I started to see that my students could accomplish so much more than I had known– that they were capable of digging into complex texts and doing the intellectual work. What’s more, the traditional engagement and participation pattern in the class was disrupted. The students who were most comfortable with ambiguity and confusion turned out to be my students who were not the typical successful students. My less experienced students were the ones most able to ask questions and explore divergent interpretations. I learned that when we, as teachers, value identifying the confusions and talking about what’s unclear, we provide an entry point for students who don’t already know it all. In fact, their questions and confusions are exactly where the inquiry needs to begin, and, in turn, our validating their contributions builds their confidence and dispositions towards doing this important work.

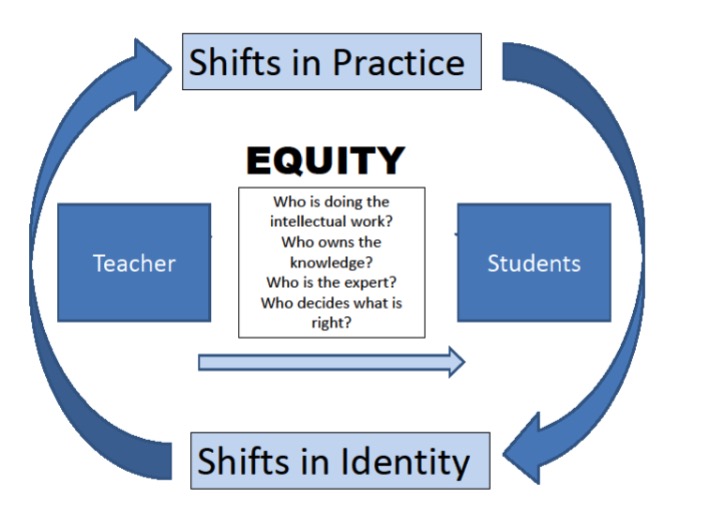

As my practices shifted, and my students took up a bigger role, other issues were called into question. “Who owns the knowledge in the room?” “Who decides what is important/right?” and “Whose interpretation counts?” If I was supporting students to engage in the practices of history by making sense of texts and developing their own interpretations, wasn’t I undermining all of that work if I swooped in with my interpretation or the canonical interpretation at the end of the process?

When I look back at video clips from the first time I tried the Iran unit, I can see how hard I am working to hold back from validating students’ interpretations and, instead, am trying to push the meaning-making back to the students. This was a huge struggle for me internally, and I got a lot of pushback from the students, which made it even harder. At one point, in a moment I like to think of as “the mutiny,” one student raised his hand to protest the “new way” of doing things. He accused me of leaving them hanging by not explaining the texts. I tried to communicate that I wanted to give them the power to decide what the texts meant for themselves. And, part of me still felt like I was guilty as charged; I wasn’t “helping,” at least not in the old way. And I didn’t yet understand the new way enough to have confidence in it. However, with Gayle’s support and encouragement, I persisted. At the end of the school year, when I looked at the video of that class for the first time, I realized the power of handing over that intellectual work to the students. Engagement was high and I could see shifts in status among the students as they worked in small groups that I hadn’t noticed in the moment.

Thus, student identities were shifting, as were my ideas about my role in teaching and learning. As I started to see myself as more of a facilitator of the learning and less the holder of the knowledge, I contemplated additional shifts that I could make in the classroom to hand over even more of the intellectual work to the students. And so, the process became, and continues to be, recursive. As I try new practices, my role shifts, which requires me to reconsider my identity as a history teacher. As my identity shifts, I reevaluate what that means about my role in the classroom and my practices.

The 2013 experience prompted me to think about the opportunity I would have in the fall with a new group of students, for the next two years: I would be able to start with routines and new practices from day one. From the beginning, students would be able to learn what it means to engage in the practices of history, to “do” history as opposed to learn historical content. At the beginning of the year, I spent almost eight weeks orienting students to the discipline of history and the reading and collaboration routines in the classroom– before we jumped into the content. I staged a fake fight and had students write eyewitness accounts, which we then ranked for trustworthiness and used to flush out sourcing skills. We worked a lot with interpretation, and I deliberately left some questions unanswered so that students could begin to learn to tolerate ambiguity. Students practiced defending their claims with evidence and working out differences until, as a group, they were satisfied with the interpretation. I did not tie things up in a bow for them at the end. At the same time, we spent a lot of class time exploring reader identities, and building the social and personal dimensions of Reading Apprenticeship. Critical to this stage was building student capacity for metacognitive discussion around reading challenges and strategies.

In order to engage students in text-based discussion, I started to push more and more of the meaning-making into my Socratic Seminars. Typically, in advance of a Socratic Seminar, students would read a text independently and I would prepare the questions. At the beginning, I would lead the discussion. But, as students became more savvy readers of history, I phased out my own involvement. I no longer provided guiding questions or facilitated the discussion. Instead, I encouraged students to ask their text-based questions and work out the puzzles and inquiries as part of their “performance.” I reflected these contributions in the rubric I used for assessment. These text-based discussions became a component of every unit and were a significant portion of their grade.

I’m proud of the work I saw students doing in 2015. The level of engagement is the product of two years of consistent routines around reading, discussion, and meaning-making. When I look back at the videos from the Iran unit in 2015, the first thing I notice is that my role in the discussion has changed. In fact, I am mostly absent. In 2013, I was repeating what students were saying to each other, just so they could hear it and put it all together. In the 2015 Jigsaw Group, for example, the students demonstrate that they believe they can figure out a complex text without the teacher needing to explain it; they are not looking to me. They persist in their own line of questioning, trying to figure out what the Coup had to do with the Cold War, and making connections across texts. They finally settle on this interpretation: the US wanted Zehedi in power because he was enemies with Mossadegh, whose supporters included the Tudeh Communist party. In order to arrive at this highly complex idea, they had placed the Coup within the context of the Cold War, successfully made sense of multiple documents and drawn from several of the texts. They view the texts, rather than the teacher, as the source of knowledge, and each other as resources for figuring things out.

Another aspect that’s really important to me in this student discourse, is that the casual observer probably cannot predict the academic status of each of the participating students. The students are not turning to the highest status straight A student, in this case Renee, to explain what the text means. In fact, the heavy lifting of questioning and making connections across text is being done by two lower status students — Ross, a reluctant student of history, and Ken, who, as was often the case, didn’t even turn in his final packet. As they go back and forth, you can see their minds at work, reaching and learning, and taking ownership of the knowledge. Jenna, a middle of the road student, pushes, confirms, and synthesizes.

In college, I had decided to become a teacher because I wanted to promote equity and work for social justice in my own community. I had always considered education to be a tool for social mobility. Through this process with READI, however, my notion of what equity means began to change. Early in my career, I saw equity as teaching students about their own potential through stories of social justice in action, illuminating counter-narratives and injustices, and motivating students to work for change. While these are important, after my work with READI, I began to see these topics as teaching about social justice rather than teaching for social justice. I now understand equity to mean offering all students the opportunity to grow as increasingly independent learners who can construct and defend their own knowledge. Today my focus is supporting the development of the skills students need in order to access content. Unlocking those skills for all students will truly open the doors to social mobility and justice because it puts the power in their hands.

References

Schoenbach, R., Greenleaf, C., & Murphy, L. (2012). Engaged academic literacy for all. In Reading for Understanding: How Reading Apprenticeship Improves Disciplinary Learning in Secondary and College Classrooms, 2nd edition (pp. 108 -110). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.